Cybercrime , Endpoint Security , Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Baltimore Ransomware Attack Triggers Blame Game

Debates Touch on NSA Exploit-Hoarding, City's Patch-Speed Failures, Windows Code Quality

Reports that the city of Baltimore was attacked using a vulnerability in Windows originally stockpiled by American intelligence agencies have triggered a blame game.

See Also: Where to Invest Next: People, Processes and Technology for Maturing Cyber Defenses

Not for the first time, the Baltimore incident has given information security watchers cause to debate questions of culpability over finding and stockpiling zero-days and exploits, as well as issues surrounding data breaches, leaks, software flaws and patch speed.

So who's at fault for the ransomware infection that has hit the city, and, more generally, attacks using the weaponized flaw exploit, code-named EternalBlue, that a number of actors continue to wield against numerous targets?

Fresh questions over culpability have resulted from a Saturday report in the New York Times that cites three former NSA operators who said the agency had spent nearly a year discovering the flaw and writing code to exploit it. The flaw was originally dubbed EternalBluescreen because it so often crashed computers. The Times reports that the exploit was used numerous times, and proved very valuable for intelligence operations over a five-year period, before the agency lost control of it. Only then did the NSA alert Microsoft to the flaw, leading to it quickly issuing patches. And now Baltimore is one of the latest victims of attackers exploiting the flaw, the Times reports.

The short list of who to potentially blame for the Baltimore incident now includes: the National Security Agency, for building the exploit and holding onto it for five years, without alerting Microsoft, before losing control of it; the shadowy group - maybe foreign, maybe domestic - calling itself the Shadow Brokers, which leaked the exploit in April 2017; Microsoft, for not building bug-free operating systems; the city of Baltimore, for having failed to apply an emergency Windows security update more than two years after it was released in March 2017 - and two months later for older operating systems - which blocked EternalBlue exploits in every Windows operation system from XP onward; and, of course, the attackers, whoever they might be.

Baltimore Gets Hit

The May 7 attack against the city of Baltimore, meanwhile, was the second ransomware outbreak to hit city systems in 14 months. In this case, the attackers used a knock-off of EternalBlue to install crypto-locking code that splashed a demand for 13 bitcoins - worth $100,000 at the time - across workers' PC screens, written in imperfect English, according to news reports.

"We've watching you for days," read a copy of the ransom demand obtained by The Baltimore Sun. "We won't talk more, all we know is MONEY! Hurry up!"

Officials have refused to pay the ransom and say they're working with the FBI as well as third-party incident responders to investigate and mitigate the attack. But three weeks after the attack, restoration operations have yet to conclude and many city operations remain suspended.

City of Baltimore officials did not immediately respond to a request for comment about whether the SMB_v1 was used to exploit city systems, and if so why they had not yet been patched.

Debate: Vulnerabilities Equities Process

Whenever someone discovers a zero-day flaw and writes code that successfully exploits it, once the code gets out in the wild, anyone can use it. For years, cybersecurity experts have been warning that every leak of a top-secret exploit allows others - from script kiddies to organized crime gangs - to also target the underlying flaw.

The U.S. government maintains a Vulnerabilities Equities Process, via which it can choose to alert vendors to code problems, so they can be patched. But for especially valuable code flaws, the government can also choose to not notify.

Thomas Rid, a cybersecurity expert at Johns Hopkins University, tells the New York Times that the Shadow Brokers leaks were "the most destructive and costly NSA breach in history" - worse even than former NSA contractor Edward Snowden's 2013 leaks - and says the U.S. government has studiously avoided taking any blame.

"The government has refused to take responsibility, or even to answer the most basic questions," Rid said. "Congressional oversight appears to be failing. The American people deserve an answer."

But other intelligence experts note that there can be clear cause for holding onto exploits. "There are substantial security benefits to retention and use and disclosure isn't always a cure," says Susan Hennessey, a senior fellow in national security at the Brookings Institution who formerly served as an attorney in the NSA's Office of General Counsel.

One element I wish we saw more analysis of is that the patch for Eternal Blue has been available since March 2017. That these attacks are still so damaging 2 years later would seem to cut against some assumptions behind mandating government disclosure of vulnerabilities. https://t.co/SmLFuvXQUR

— Susan Hennessey (@Susan_Hennessey) May 25, 2019

EternalBlue Knockoffs

While this might be splitting hairs, attackers often don't use the exact EternalBlue tool to attack targets. David Maynor, a security researcher at Cisco Talos, notes that attackers typically use "a knocked off copy" of the exploit code "written after the leak" to target the SMB_v1 flaw. Regardless, targeting the flaw is the point, and the flaw didn't come to public attention until the Shadow Brokers leaked it in April 2017.

Since then, attacks that utilize the flaw have been blamed on apparent criminal gangs as well as nation-state attackers. North Korea was allegedly behind crypto-mining attacks as well as the WannaCry outbreak that began in May 2017 and exploited the flaw in a worm-like fashion (see After 2 Years, WannaCry Remains a Threat).

Russia, meanwhile, has been blamed for launching NotPetya, which targeted the SMB_v1 flaw.

Earlier this month, however, a report from Symantec said Chinese attackers were targeting the flaw before the Shadow Brokers ever leaked it. That suggests intelligence agencies beyond the NSA knew about the flaw and were targeting it before Microsoft received a heads-up from the U.S. government and rushed out patches.

Baltimore Failed to Patch

So for more than two years, why hadn't Baltimore patched its systems against the SMB_v1 vulnerability that EternalBlue exploited, despite global alerts about the severity of the flaw? Robert Graham, head of offensive security firm Errata Security, says the city is clearly at fault for not doing so. He also stresses that the SMB_v1 exploit is just one tool in attackers' attack toolkit, and that they'll use whatever works. And so long as it works, they'll keep using it.

Eternalblue was released over two years ago.. If an organization has substantial numbers of Windows machines that have gone 2 years without patches, then that's squarely the fault of the organization, not Eternalblue.

— Rob Graham (@ErrataRob) May 25, 2019

Likewise, Beau Woods a cyber safety innovation fellow with the Atlantic Council, says one of the main takeaways from the WannaCry outbreak - and now the recent Baltimore ransomware attack - is that attackers will use whatever works.

Two years after #WannaCry, and #NotPetya, this thread is more true. Focus on a specific exploit is short sighted. Adversaries understand this and adopt new exploit modules to stay ahead of defenders. Why is @nytimes still writing the same story today? https://t.co/pUmoHNlxeF

— Beau Woods (@beauwoods) May 27, 2019

Patch or Perish Redux

Patching is the obvious fix. But patching isn't easy, or else everyone would be experts at it, and exploits of a well-publicized and long-patched SMB_v1 flaw in Windows would never succeed (see Why Attackers Keep Winning at 'Patch or Perish').

"For some organizations, patching can be a non-trivial exercise, even with a couple of years of lead time," data breach expert Troy Hunt tells the BBC.

"Specialized systems such as medical devices, for example, often go unpatched for long periods of time," he says. "Given we're still seeing infections due to EternalBlue two years after it was patched, evidently there are still systems out there both unpatched and exposed."

Hunt says he's surprised that large organizations such as the city of Baltimore are continuing to get exploited via unpatched SMB_v1.

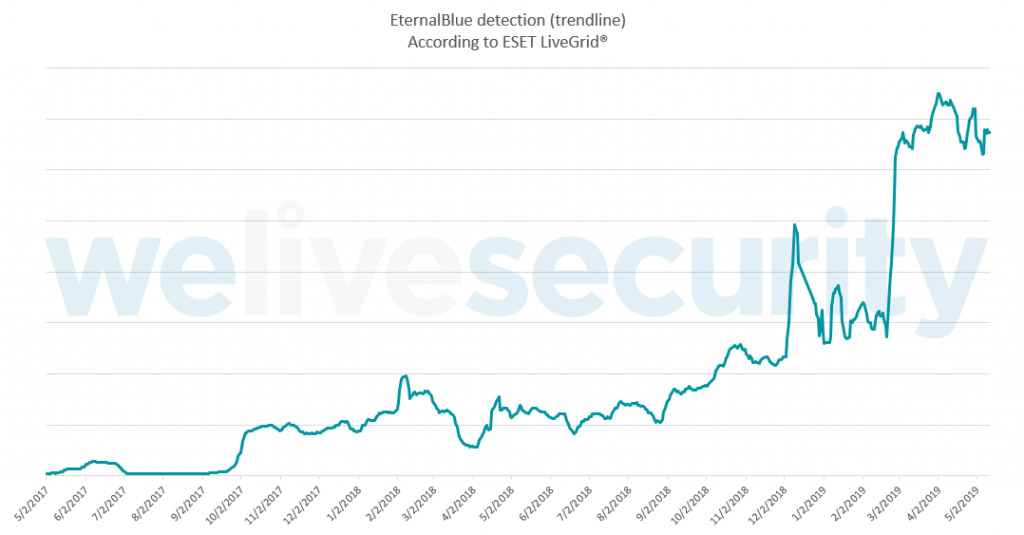

But Baltimore is far from the only entity that appears to be behind on its Windows SMB_v1 patching. And security firm ESET reports that more attackers than ever have been searching for vulnerable systems.

Blame Attackers

When it comes to disrupting Baltimore, Robert M. Lee, a former U.S. Air Force cyber warfare operations officer who's now CEO of industrial control system security firm Dragos, says attackers are clearly to blame, regardless of which exploits they might be using or who may have discovered them first.

And as much as I'm willing to critique plenty of things about the NSA, they are far more transparent than other government's intelligence agencies and actually have things like vulnerability equities processes. Unpopular take: they deserve a lot of credit for that.

— Robert M. Lee (@RobertMLee) May 25, 2019

"NSA seems to get blamed for everything," Lee tweets. "They deserve blame and critique for some things. But not for everything, and two years after an exploit is patched, it feels to me that we should focus more on the adversary than the origin of an exploit."